CHAPTER XII

THE BÁB'S JOURNEY FROM KÁSHÁN TO TABRIZ

ATTENDED by His escort, the Báb proceeded in the direction of Qum. 1 His alluring charm, combined with a compelling dignity and unfailing benevolence, had, by this time, completely disarmed and transformed His guards. They seemed to have abdicated all their rights and duties and to have resigned themselves to His will and pleasure. In their eagerness to serve and please Him, they, one day, remarked: "We are strictly forbidden by the government to allow You to enter the city of Qum, and have been ordered to proceed by an unfrequented route directly to Tihrán. We have been particularly directed to keep away from the Haram-i-Ma'súmih, 2 that inviolable sanctuary under whose shelter the most notorious criminals are immune from arrest. We are ready, however, to ignore utterly for Your sake whatever instructions we have received. If it be Your wish, we shall unhesitatingly conduct You through the streets of Qum and enable You to visit its holy shrine." "'The heart of the true believer is the throne of God,'" observed the Báb. "He who is the ark of salvation and the Almighty's impregnable stronghold is now journeying with you through this wilderness. I prefer the way of the country rather than to enter this unholy city. The immaculate one whose remains are interred within this shrine, her brother, and her illustrious ancestors no doubt bewail the plight of this wicked people. With their lips they pay homage to her; by their acts they heap dishonour upon her name. Outwardly they serve and reverence her shrine; inwardly they disgrace her dignity."

2. "At Qum are deposited the remains of his [Imám Ridá's] sister, Fátimiy-i-Ma'súmih, i.e. the Immaculate, who, according to one account, lived and died here, having fled from Baghdád to escape the persecution of the Khalífs; according to another, sickened and died at Qum, on her way to see her brother at Tus. He, for his part, is believed by the pious Shí'ahs to return the compliment by paying her a visit every Friday from his shrine at Mashhad." Lord Curzon's "Persia and the Persian Question," vol. 2, p. 8.)

They were planning to reach the capital on the ensuing day, and had decided to spend the night in the neighbourhood of that fortress, when a messenger unexpectedly arrived from Tihrán, bearing a written order from Hájí Mírzá Aqásí to Muhammad Big.

That message instructed him to proceed immediately with the Báb to the village of Kulayn, 4 where Shaykh-i-Kulayní, Muhammad-ibn-i-Ya'qub, the author of the Usul-i-Káfí, who was born in that place, had been laid to rest with his father, and whose shrines are greatly honoured by the people of that neighbourhood. 5 Muhammad Big was commanded, in view of the unsuitability of the houses in that village, to pitch a special tent for the Báb and keep the escort in its neighbourhood pending the receipt of further instructions. On the morning of the ninth day after Naw-Rúz, the eleventh day of the month of Rabí'u'th-Thání, in the year 1263 A.H., 6 in the immediate vicinity of that village, which belonged to Hájí Mírzá Aqásí, a tent which had served for his own use whenever he visited that place was erected for the Báb, on the slopes of a hill pleasantly situated amid wide stretches of orchards and smiling meadows. The peacefulness of that spot, the luxuriance of its vegetation, and the unceasing murmur of its streams greatly pleased the Báb. He was joined two days after by Siyyid Husayn-i-Yazdí, Siyyid Hasan, his brother; Mullá 'Abdu'l-Karím, and Shaykh Hasan-i-Zunúzí, all of whom were invited to lodge in the immediate surroundings of His tent. On the fourteenth day of the month of Rabí'u'th-Thání, 7 the twelfth day after Naw-Rúz, Mullá Mihdíy-i-Khú'í and Mullá Muhammad-Mihdíy-i-Kandí arrived from Tihrán. The latter, who had been closely associated with Bahá'u'lláh in Tihrán, had been commissioned by Him to present to the Báb a sealed letter together with certain gifts which, as soon as they were delivered into His hands, provoked in His soul sentiments of unusual delight. His face glowed with joy as He overwhelmed the bearer with marks of His gratitude and favour.

4. See "A Traveller's Narrative," p. 14, note 3.

5. "As the order of the prime minister Hájí Mírzá Aqásí became generally known, it was impossible to carry it out. From Isfahán to Tihrán, everyone spoke of the iniquity of the clergy and of the government towards the Báb; everywhere the people muttered and exclaimed against such an injustice." (Journal Asiatique, 1866, tome 7, p. 355.)

6. March 29, 1847 A.D.

7. April 1, 1847 A.D.

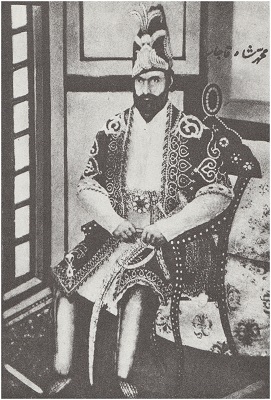

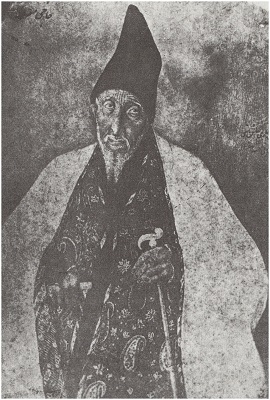

10. "Muhammad Sháh," writes Gobineau, "was a prince of peculiar temperament, a type often seen in Asia but not often discovered or understood by Europeans. Although he reigned during a period when political practices were rather harsh, he was kind and patient and his tolerance extended even to the discords of his harem which were of such a nature as normally to cause grave annoyance; for, even in the days of Fath-'Alí Sháh, the laisser-aller, the whims and fancies were never carried to such an extreme. The following words which our 18th century might recognize as its own are attributed to him: 'Why are you not more discreet, Madam? I do not wish to hinder you from enjoying yourself.' "But, in his case, it was not affected indifference, but fatigue and boredom. His health had always been wretched; seriously ill with gout, he was hardly ever free from pain. His disposition naturally weak, had become very melancholy and, as he craved love and could not find it in his family either with his wives or children, he had centered all his affection upon the aged Mullá, his tutor. He had made of him his only friend, his confidant, then his first and all-powerful minister, even his god! Brought up by this idol with very irreverent sentiments toward Islám, he was equally as indifferent toward the dogmas of the Prophet as toward the Prophet himself. He cared little for the Imáms and, if he had any regard for 'Alí, it is because the Persian mind is wont to identify this venerable personage with the nation itself. "But in brief, Muhammad Sháh was no better Muhammadan than he was Christian or Jew. He believed that the Divine Essence incarnates Itself in the Sages with all Its power, and, as he considered Hájí Mírzá Aqásí a Sage par excellence, he felt certain that he was God and he would piously ask him to perform miracles. Often he said to his officers with earnestness and conviction, 'The Hájí has promised me a miracle for tonight, you shall see!' As long as the character of the Hájí was not involved, Muhammad Sháh was completely indifferent regarding the success or failure of this or that religious doctrine; he was rather pleased to witness the conflict of opinions which were proof to him of the universal blindness." (Comte de Gobineau's "Les Religions et les Philosophies dans l'Asie Centrale,' pp. 131–2.)

11. According to "A Traveller's Narrative" (p. 14), the Báb "forwarded a letter to the Royal Presence craving audience to set forth the truth of His condition, expecting this to be a means for the attainment of great advantages." Regarding this letter, Gobineau writes as follows: "'Alí-Muhammad wrote personally to the Court and his letter and the accusations of his adversaries all arrived at the same time. Without assuming an aggressive attitude toward the king, but trusting on the contrary to his authority and justice, he represented to them that the depravity of the clergy in Persia had been well known for many years; that not only morals were thereby corrupted and the well-being of the nation affected, but that religion itself, poisoned by the sins of so many, was in great danger and was about to disappear leaving the people in perilous darkness. "As for himself, called by God, in virtue of a special mission, to prevent such an evil, he had already begun to apprise the people of Fárs that the true doctrine had made evident and rapid progress; that all its adversaries had been confounded and were now powerless and universally despised; but that this was only a beginning. "The Báb, confident of the magnanimity of the king, requested the permission to come to the capital with his principal disciples and there hold conferences with all the Mullás of the Empire, in the presence of the Sovereign, the nobles and the people, convinced that he would shame them by exposing their faithlessness. He would accept beforehand the judgment of the king and, in case of failure, was ready to sacrifice his head and that of each one of his followers." (Comte de Gobineau's "Les Religions et les Philosophies dans l'Asie Centrale," p. 124.)

12. March 19-April 17, 1847 A.D.

Incapable of being admonished by the example of his predecessors, he contemptuously ignored the demands and interests of the people, pursued, with unremitting zeal, his designs for personal aggrandisement, and by his profligacy and extravagance involved his country in ruinous wars with its neighbours. Sa'd-i-Ma'adh, who was neither of royal blood nor invested with authority, attained, through the uprightness of his conduct and his unsparing devotion to the Cause of Muhammad, so exalted a station that to the present day the chiefs and rulers of Islám have continued to reverence his memory and to praise his virtues; whereas Buzurg-Mihr, the ablest, the wisest and most experienced administrator among the vazírs of Nushiravan-i-'Adil, in spite of his commanding position, eventually was publicly disgraced, was thrown into a pit, and became the object of the contempt and the ridicule of the people. He bewailed his plight and wept so bitterly that he finally lost his sight. Neither the example of the former nor the fate of the latter seemed to have awakened that self-confident minister to the perils of his own position. He persisted in his thoughts until he too forfeited his rank, lost his riches, 18 and sank into abasement and shame. The numerous properties which he forcibly seized from the humble and law-abiding subjects of the Sháh, the costly furnitures with which he embellished them, the vast expenditures of labour and treasure which he ordered for their improvement—all were irretrievably lost two years after he had issued his decree condemning the Báb to a cruel incarceration in the inhospitable mountains of Ádhirbayján. All his possessions were confiscated by the State. He himself was disgraced by his sovereign, was ignominiously expelled from Tihrán, and fell a prey to disease and poverty. Bereft of hope and sunk in misery, he languished in Karbilá until the hour of his death. 19

14. "An anecdote shows the real motive of the prime minister in the suggestions he made to the Sháh concerning the Báb. The Prince Farhád Mírzá, still young, was the pupil of Hájí Mírzá Aqásí. The latter related the following story: "When His Majesty, after consulting the prime minister, had written to the Báb to betake himself to Máh-Kú, we went with Hájí Mírzá Aqásí to spend a few days at Yáft-Ábád, in the neighborhood of Tihrán, in the park which he had created there. I was very desirous of questioning my master regarding the recent happenings but I feared to do so publicly. One day, while I was walking with him in the garden and he was in a good humor, I made bold to ask him: "Hájí, why have you sent the Báb to Máh-Kú?" He replied,—"You are still too young to understand certain things, but know that had he come to Tihrán. you and I would not be, at this moment, walking free from care in this cool shade."'" (A. L. M. Nicolas' "Siyyid 'Alí-Muhammad dit le Báb," pp. 243–244) According to Hájí Mu'inu's-Saltanih's narrative (p. 129), the chief motive which actuated Hájí Mírzá Aqásí to urge Muhammad Sháh to order the banishment of the Báb to Ádhirbayján was the fear lest the promise which the Báb had given to the sovereign that He would cure him of his illness, were he to allow Him to be received in Tihrán, should be fulfilled. He felt sure that should the Báb be able to effect such a cure, the Sháh would fall under the influence of his Prisoner and would cease to confer upon his prime minister the honours and benefits which he exclusively enjoyed.

15. According to Mírzá Abu'l-Fadl, Hájí Mírzá Aqásí sought, by his reference to the rebellion of Muhammad Hasan Khán, the Salar, in Khurásán, and the revolt of Áqá Khán-i-Isma'ílí, in Kirmán, to induce the sovereign to abandon the project of summoning the Báb to the capital, and to send Him instead to the remote province of Ádhirbayján.

16. "Nevertheless, on this occasion, his expectations did not materialize. Fearing that the presence of the Báb in Tihrán would occasion new disturbances (there were plenty of them due to his whims and his poor administration), he altered his plans and the escort, charged to take the Báb from Isfahán to Tihrán, received, when about thirty kilometers from the city, the order to take the prisoner directly to Máh-Kú. This town, in the mind of the prime minister, would offer nothing to the impostor because its inhabitants, out of gratitude for the favors and protection they had received from him, would take steps to suppress any disturbances which might break out." (Journal Asiatique, 1866, tome 7, p. 356.)

17. "The state of Persia, however, was not satisfactory; for Hájí Mírzá Aqásí, who had been its virtual ruler for thirteen years, 'was utterly ignorant of statesmanship or of military science, yet too vain to receive instruction and too jealous to admit of a coadjutor; brutal in his language; insolent in his demeanour; indolent in his habits; he brought the exchequer to the verge of bankruptcy and the country to the brink of revolution. The pay of the army was generally from three to five years in arrears. 'The cavalry of the tribes was almost annihilated.' Such—to adopt the weighty words of Rawlinson—was the condition of Persia in the middle of the nineteenth century." (P. M. Sykes' "A History of Persia," vol. 2, pp. 439–40.)

18. "Hájí Mírzá Aqásí, the half crazy old Prime Minister, had the whole administration in his hands, and obtained complete control over the Sháh. The misgovernment of the country grew worse and worse, while the people starved, and cursed the Qájár dynasty…. The condition of the province was deplorable and every man with any pretension to talent or patriotism was driven into exile by the old haji, who was sedulously collecting wealth for himself at Tihrán, at the expense of the wretched country. The governorships of provinces were sold to the highest bidders, who oppressed the people in a fearful manner." (C. R. Markham's "A General Sketch of the History of Persia," pp. 486–7.)

19. Gobineau writes regarding his fall: "Hájí Mírzá Aqásí, robbed of the power which he had constantly ridiculed, had retired to Karbilá and he spent his remaining days playing tricks on the Mullás and scoffing even at the holy martyrs." ("Les Religions et les Philosophies dans l'Asie Centrale," p. 160.) "This shrewd man had gained such power over the late Sháh that one could truly say that the minister was the real sovereign; he could not therefore survive the loss of his good fortune. At the death of Muhammad Sháh, he had disappeared and had gone to Karbilá where, under the protection of the sainted Imám, even a state criminal could find an inviolable asylum. He was soon overcome by gnawing grief which, more than his remorse; shortened his life." (Journal Asiatique, 1866, tome 7, pp. 367–8.)

21. According to Samandar (manuscript, pp. 45), the Báb tarried in the village of Síyáh-Dihán, in the neighbourhood of Qazvín, on His way to Ádhirbayján. In the course of that journey, He is reported to have revealed several Tablets addressed to the leading 'ulamás in Qazvín among whom were the following: Hájí Mullá 'Abdu'l-Vahháb, Hájí Mullá Sálih, Hájí Mullá Taqí, and Hájí Siyyid Taqí. These Tablets were conveyed to their recipients through Hájí Mullá Ahmad-i-Ibdal. Several believers, among whom were the two sons of Hájí Mullá 'Abdu'l-Vahháb were able to meet the Báb during the night He spent in that village. It is from this village that the Báb is reported to have addressed His epistle to Hájí Mírzá Aqásí.

To each the Báb expressed His appreciation of his devoted attentions and assured him of His prayers in his behalf. Reluctantly they delivered Him into the hands of the governor of Tabríz, the heir to the throne of Muhammad Sháh. To those with whom they were subsequently brought in contact, these devoted attendants of the Báb and eye-witnesses of His superhuman wisdom and power, recounted with awe and admiration the tale of those wonders which they had seen and heard, and by this means helped to diffuse in their own way the knowledge of the new Revelation.

|

|

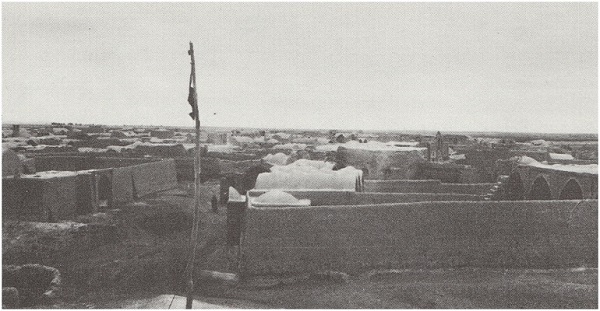

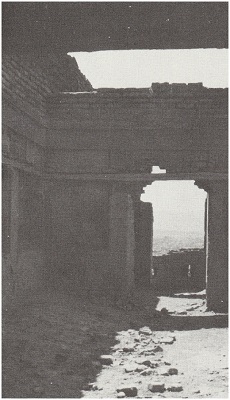

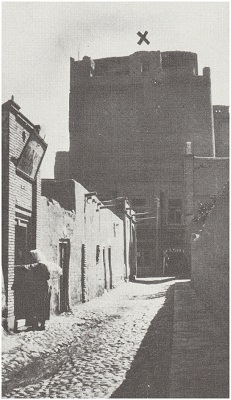

THE ARK (CITADEL) OF TABRÍZ WHERE THE BÁB WAS CONFINED, SHOWING

INTERIOR AND EXTERIOR (X) OF ROOM HE OCCUPIED

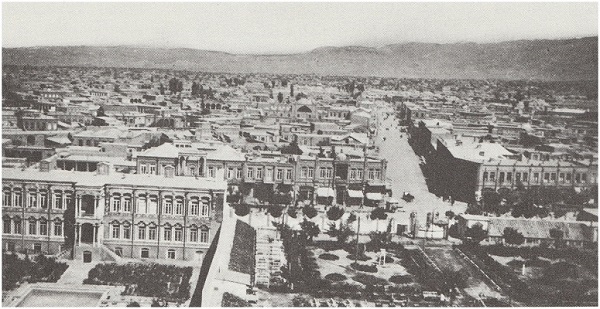

A detachment of the Násirí regiment stood guard at the entrance of His house. With the exception of Siyyid Husayn and his brother, neither the public nor His followers were allowed to meet Him. This same regiment, which had been recruited from among the inhabitants of Khamsíh, and upon which special honours had been conferred, was subsequently chosen to discharge the volley that caused His death. The circumstances of His arrival had stirred the people in Tabríz profoundly. A tumultuous concourse of people had gathered to witness His entry into the city. 26 Some were impelled by curiosity, others were earnestly desirous of ascertaining the veracity of the wild reports that were current about Him, and still others were moved by their faith and devotion to attain His presence and to assure Him of their loyalty. As He walked along the streets, the acclamations of the multitude resounded on every side. The great majority of the people who beheld His face greeted Him with the shout of "Alláh-u-Akbar," 27 others loudly glorified and cheered Him, a few invoked upon Him the blessings of the Almighty, others were seen to kiss reverently the dust of His footsteps. Such was the clamour which His arrival had raised that a crier was ordered to warn the populace of the danger that awaited those who ventured to seek His presence. "Whosoever shall make any attempt to approach the Siyyid-i-Báb," went forth the cry, "or seek to meet him, all his possessions shall forthwith be seized and he himself condemned to perpetual imprisonment."

26. "The success of this energetic man, Mullá Yúsúf-i-Ardibílí, was so great and so swift that, at the very gates of Tauris (Tabríz), the inhabitants of this populous village acknowledged him as their leader and took the name of Bábí's. Needless to say that, in the town itself, the Bábí's were quite numerous, even though the government was taking steps to convict the Báb, to punish him and thereby justify itself in the eyes of the people." (Journal Asiatique, 1866, tome 7, pp. 357–8.)

27. "God is the Most Great."